Imola Antal Mavity

Landscapes of the mind

The paintings of Nicholas Jones quite unmistakably depict landscape, his work continuing the great English tradition of the genre. However, whilst oil is applied to his canvases with the diligence of the masters, the viewpoint of the artist’s eye has entirely changed. Reminiscent of Turner’s passionate interpretations of nature described by his critics as mere fantasies in “soapsuds and whitewash” 1, Jones’ paintings preserve the highly personal and abstracted quality of what – in the case of both painters (yet on different levels) – could be defined as ‘landscapes of the mind’. (Fig. 1)

However, Jones, like most contemporary landscapists, moves away from all that is literal in the depiction of a landscape and, instead, promotes a certain idea or mental echo of a landscape, perceived on a much more personal level. As he admits:

What I’m trying to do is to produce images that evoke and distil the experience of landscape – not a literal reproducing, but more the feeling of what it’s like to be in a particular place.2

From a visual point of view, his sensitive records of nature’s delicacies are reminiscent of impressionist practices. Subtleties of hue and texture dissolve into diaphanous vistas, opening up his paintings and allowing them to breathe. In them, night turns into day, shade into light, an ordinary landscape into an exquisite moment of still beauty, infused with poetic resonances. His silent landscapes seem to be more a creation of vapour, mist, spray and splashes, than the work of the artist’s hand. Jones’ serene outlook on life and his unsophisticated view of his work give his pieces the quality of freshly discovered miracles.

Whilst they contain echoes of the Romantics and Turner in particular, the transformations in Jones’ artistic outlook could also be explained by our painter’s quiet, serene character. His vistas are predominantly static and tend to depict a corner of nature witnessed from an intimate angle, whereas Turner’s wide panoramas often picture landscapes which are dynamic and flamboyant, and are obviously designed to leave the viewer awestruck by the sublime grandeur of nature. In spite of this, this chapter will seek to show how Turner’s vocabulary and techniques have inspired the use of light in Jones’ paintings. Other influences will also be examined.

A critical analysis of Nicholas Jones’ work can be challenging, due to its highly aesthetic appeal. Therefore, if the study undertaken in this chapter offers a rather subjective reading, it is because the artist’s work triggers such an individual response in each viewer in turn. Beauty needs no label. It is there for everybody to see and enjoy. It also often does not need a structure and has no logic; it is more like a balm soothing to our senses and we get pleasure from it almost immediately, without feeling the need to explain its effect or analyse our reactions.

My interview with the painter proved this point. He talked about his work sparsely and timidly, as if demonstrating a strictly personal interest, almost oblivious of the fact that it is regularly on display in an important London gallery for viewers to admire and scrutinise. Nevertheless, the flicker of excitement in his eyes when he describes how a work “comes alive” in the studio, betrays a deep passion for painting. To Nicholas Jones, a piece is successful only if it manages to move the viewer:

I would be pleased if I could paint something that would make people catch their breath. If I could explain in words exactly what I was trying to achieve there would perhaps be no need to paint it. 3

The artist’s sensibility is like a harp which vibrates at the slightest touch – each breath of air produces a sound. The smallest stimulus from the outside has a significant impact on the process of creation. The moment when all notes blend into a harmony is when a work of art “comes alive”. It seems that Jones’ work triggers lyrical associations unawares. Writing about it would in fact best be done in verse, for only poetry has the ability to reproduce inherent rhythms and describe the indescribable. Jones admits that it is difficult to talk about something that is part of him – self-analysis does not come easy to most of us. For this reason, he turns to poetry, very close in conception to the way he works – stimulated by his emotions and a keen aesthetic drive.

I sometimes dip into poetry: Basho, R. S. Thomas, nature writer Annie Dillard who looked at nature at such a deep level. With all the business of family life it can be difficult to focus when I get into the studio. Sometimes I find that reading haiku creates a sense of stillness and helps reconnect me to that intense way of experiencing landscape. 4

Jones’ lyrical preferences are there to help visualise his landscapes. The artist mentions three different types of poetry written at very different times. However, it is notable that all can be characterised by a predominant simplicity and the elimination of the metaphor used in the conventional English literary tradition. Basho’s verse is minimal, R. S. Thomas’ language is raw, and Dillard reinvents the notion of the metaphor altogether. The important thing is that none of their work is artificially adorned with superfluous figures of speech. Although by reading their work, one might conjure up metaphorical associations and powerful imagery, the language producing these is clear cut, candid and unpretentious. It is no surprise, therefore, when we discover that all these characteristics apply to Jones’ landscapes. Although the artist unassumingly describes the sensational act of creation as “simply just painting” – sometimes even putting it down to the lucky outcomes of clumsy efforts – almost every image he produces thrills our senses through its sheer beauty, balance and lyricism. (Fig. 2)

A brief parallel between some of the above-mentioned poetry and Jones’ painting might help towards a more intuitive reading of the lyrical connotations transpiring in his landscapes. At first sight, numerous direct visual associations could be made between his pictures and Japanese haiku, which gives concise clues for a wide range of landscape imagery, like, for instance, this poem by Basho, referred to in later comments:

This first fallen snow

Is barely enough to bend

The jonquil leavesBasho Matsuo

1644 – 1694)

Considering further parallels between Jones’ landscapes and Eastern art (such as Japanese prints) discussed later in this chapter, it might be of some assistance to introduce this form of poetry and the aesthetic context which generated it. Several differences between Western and Eastern aesthetics will transpire from this analysis.

Haiku is a small form of poetry with oriental metric, rendered in English as three unrhymed lines usually totalling seventeen syllables. It appeared in Japan in the sixteenth century, and was disseminated all around the world. Its history is reminiscent of spiritualist philosophy, the Taoist symbolism of the oriental mystics and Zen Buddhist masters who express much of their thoughts in form of myths, symbols, paradoxes and poetic images.

Art as communication is a notion central to Western aesthetics, as is the resulting interrelationship of form and content. (Without such rapport there is no logic, which makes communication impossible.) Also, in the West, music is regarded as a means of expressing emotions and consists of “sonorous moving forms” 5. In the Western tradition, a landscape painting is not solely an aesthetically pleasing reproduction; the artist uses his techniques of balance, perspective and colour to convey a personal reaction to the scenery – such painting immortalizes human mood. The aesthetic object presented to the viewer is taken to be an embodiment of the artist’s feelings. All the painter’s technical efforts are directed towards creating an illusion of reality.

In the East, on the other hand, the Zen artist tries to capture the essence of the object by the simplest possible means. Anything may be painted, or expressed in poetry, and any sounds may become music. The task of the artist is to suggest the eternal qualities of the object. The latter is a natural work of art in itself, even before it is found and adopted as an object of contemplation. For instance, in Basho’s haiku, the ‘jonquil leaves’ would have a resilience and beauty of their own, even if the poet’s eyes had never come across them. In order to achieve a perfect work of art, the artist must fully understand the inner nature of the object, its Buddha nature. Basho’s haiku too focuses, therefore, on a single elemental detail of nature – the lightness of the first fallen snow. Comprehending the essence of a movement is the hard part. Technique, though important, is useless without it; and the actual execution of the art work may be amazingly spontaneous, once the artist has identified with the spirit of his subject. This is how, ultimately, only seventeen syllables of a haiku are enough to effectively feed our imagination. Jones loves the precise simplicity of the images suggested, the remarkable power of haiku to transport the reader into a particular setting:

Haiku instantly evokes a very specific experience in such a simple way … I would like my painting to have a similar effect, capturing very specific experiences; a leaf falling or the sound of rain on water … 6

Concentrated experience is what the painter is seeking. The sheer, undiluted essence of a simple moment in time is filtered by his sensibility and recorded on canvas – hence elements of Eastern and Western aesthetics merge in his work. On the one hand, we have the artist wishing to capture the spirit of a certain place (his portrayed object); on the other hand, Jones, an exponent of the grand English tradition, cannot suppress communicating his own emotional response to the landscape. Although the tendency of creating an illusion of reality in the proper Western tradition is eliminated when figuration disappears, painting as an expression of human emotions remains central to Jones’ landscapes.

Let us take for instance this depiction of a flower opening. (Fig. 3, & Fig. 4) With Jones, the essence of the moment is rendered by a combination of colour intensity, light and dynamic marks which reflect the artist’s unique personal touch. The Japanese ukio-e artist Hiroshige, on the other hand, adopts a different approach in order to reach the same end-result: capturing the inherent nature of a blooming flower. In achieving this, he uses figuration, simplicity of line and economy of colour; meanwhile, his picture is somewhat impersonal, giving away very little of his personality or emotional predisposition when creating it. The calligraphy is probably the most personal mark in the picture.

Here are two ways of looking at the same subject. Common features are the focus on a small detail in nature and the aesthetic appeal of both images. They greatly differ, however, as far as technique and expressivity are concerned. The Japanese print is a very skilful record of essential, defining traits of an object from observed reality, whereas Jones’ abstract adopts the subject as a pretext for imparting his emotional reaction.

The swift lines of the haiku may evoke a landscape vision, but can also sum up and define what Jones has already captured in his images:

The titles are sometimes inspired by haiku but I only think of them after the painting is finished. Sometimes my brother Bill, a poet, comes over and we think up titles together. Some artists don’t bother with them but I feel that they are like handles on the work. They can give people a way into the painting.

So, instead of an automatic labelling process (e.g. numbering abstracts, like other artists), finding titles for Jones’ images becomes a creative adventure. The artist’s work is not finished once he stops painting. The transformation continues in the way he perceives and starts reading meanings into the final cohesive picture. Once he has established that it works on a compositional and chromatic – thus, ultimately, on an aesthetic – level, it is time to put ‘handles’ on it, to suggest to the viewer one of many ways of approaching the picture. The moment of clarification equally benefits the artist himself; it enables him to step back, take in what he has produced and therefore appropriate it before it becomes everybody else’s experience. Once this process has been completed, he can embark on a new set of projects with the same purpose.

Jones’ willingness to provide potential clues for the reading of his images denotes his generosity with regard to imparting his feelings of a certain place to the viewer. His dreamy titles include such formulae as these: The Smallest Breath, Night Smoke, The Face of the Waters, Last Light, The Silk of the Wind. Along with the rich imagery and colour scheme, these titles make his work a pleasing and, most importantly, accessible experience to most spectators. It is obvious that Jones is idealising nature, beautifying it. All of a sudden, the abstract-figurative barrier subsides and viewers of all ages and preconceptions are universally drawn into his welcoming vistas.

Just like haiku, Jones’ landscapes allow us a glimpse of a very normal, everyday aspect of nature: the innocent outlook on nature’s smallest occurrences preserves the primordial purity of the setting. Unlike many contemporary abstract landscapes, Jones’ are wonderfully static, suggesting quiet introspection and meditation.

the crescent lights

the misty ground

buckwheat flowersBasho Matsuo

(1644 – 1694)

Let us imagine how such a poem could inspire a landscape painting. It is easy to find a haiku which could best be juxtaposed to Jones’ abstract. Let us take, for instance Basho’s poem above: the poem complements the image in Coastline, Rain and Sunlight (Fig. 5) perfectly, potentially having the same role as the titles – as it were, showing a way into the landscape. The succinct lines provide a variety of visual projections and Coastline Rain and Sunlight could be one of them. Although metaphor in the traditional literary sense is missing from the haiku, which rather turns it into an enumeration of nature’s elements, it is in fact more present than in any other poem. The metaphor is written ‘with invisible ink’ into it, connecting its constituent parts to form an inclusive picture. This very quality might be what the painter would like to achieve in his work. No straightforward, literal associations, just hints and glimpses which will eventually come together in our minds as constituent parts of a landscape.

The three lines of the haiku cover tree planes of the picture; the upper plane; the lights; the middle; the ground; and the lower; the flowers. The beauty of abstract landscapes is that they are open to countless interpretations. Should one attempt to read this particular haiku into Nicholas Jones’ painting, one would immediately discover the back-lit effect of the sky in the upper part of the picture achieved through variations in colour intensity and contrast. Pigment is applied in layers of different quality, in compact, opaque or transparent areas and it is interesting how a rosy veil seems to migrate towards the centre of the landscape, creating a “misty ground”. Finally, blobs of light pigment are added, presumably to depict flowers cropping up on the coastline. In reality, however, Jones’ landscape is very much a ‘drip and splash’ product and on close inspection we come across areas where paper had been laid on the canvas, then peeled off and diluted pigment poured or dribbled onto it. Thus, unconventional techniques are used to depict a very traditional subject.

On the whole, the haiku poet, like Jones, can imbue any landscape with poetic feeling, once that landscape has been appreciated aesthetically. Its verses transcend the limitations imposed by everyday language and the linear/scientific patterns of thinking that treat nature and the human being as machines. Its contemplative lines give much value to colour, season, contrasts and surprises in nature. Like a snapshot, it captures a moment, sensation, impression or drama arising from a specific fact. In order to compose a real haiku, more than inspiration is needed – one has to reach a profound level of meditation, effort and perception. Basho asserted that things seemingly useless had the real value, and that it was the right way of life not to go against the natural law. He infused a mystical quality into much of his verse and attempted to express universal themes through simple natural images, from the harvest moon to the fleas in his cottage. “Do not follow in the footsteps of the old masters, but seek what they sought”, was his motto. Jones’ outlook on art seems to work very much in line with Basho’s advice. He specifies from the onset that he does not see himself as belonging to any style or tradition. The fact that he lives and works near his native Bristol, somewhat isolated from the “madding crowd” of his contemporaries might explain Nichols Jones’ unique style, plastic in an almost old-fashioned painterly sense, in spite of its technical freshness.

Amongst his favourite poets, Jones also mentions Ronald Stuart Thomas (1913- 2000). Quite interestingly, during his life, the Welsh poet himself had developed an interest in the relations between the visual and the verbal. He published four separate volumes between 1977 and 1985 that explored this relationship, sometimes directly and sometimes more obliquely. In The Way of It (1977), his poems are set beside drawings by Barry Hirst (b. 1934), pointing out the close relationship between the two types of artefact. In Between Here and Now (1981) however, the relationship is much more direct since most of the poems are commentaries on Impressionist paintings from the Louvre, illustrated in black and white alongside the text. Later, in Ingrowing Thoughts (1985), Thomas’ poems are directly inspired by surrealist and other modern paintings accompanying the text, and in Destinations by reproductions of paintings by Paul Nash (1889 – 1946) completed in the 1920s.

Thomas’ imagination was clearly fired by visual images, whether as a direct inspiration for his own composition, or in the hope that the chosen pictures would excite the reader/viewer. Jones finds a similar source of creative stimulation through the reverse process – reading the poet brings forth images and the mood for painting them. But how does his work relate to Thomas’ poetry? His verses are generally marked by an overwhelming fascination with the harsh, bleak landscape of rural Wales and how this has shaped the character of her people. His poems are uncompromising, his images like slate – hard and sharp, his style spare, fearless, and honest. He has the ability to impart his hermit-like identification with an unyielding landscape; always tempered, though, by intellect. Let us consider one of Thomas’ poems alongside a painting by Jones:

The View from the Window

Like a painting it is set before one,

But less brittle, ageless; these colours

Are renewed daily with variations

Of light and distance that no painter

Achieves or suggest. Then there is movement,

Change, as slowly the cloud bruises

Are healed by sunlight, or snow caps

A black mood; but gold at evening

To cheer the heart. All through history

The great brush has not rested,

Nor the paint dried; yet what eye,

Looking coolly, or, as we now,

Through the tears’ lenses, ever saw

This work and it was not finished?R. S. Thomas 7

Thomas here clearly contrasts the making of the world we live in with the making of the work of art – the landscape we inhabit, with the landscape depicted by a painter. His title (The View from the Window) already frames the view described, as would the frame of a painting. The Welsh priest meditates on the transience of life as it is contrasted with the permanence of the Divine “great brush” that has created everything. He is awestruck by the timeless perfection of nature, which art can never fully replicate.

It is interesting to see how both poet and painter differentiate between the static and dynamic aspects of nature. Thomas also makes a distinction between fleeting, more superficial changes, like for instance, the shape of clouds, and the more permanent ones related to the evolution and alteration of the general landscape.

In Jones’ Winter Flight (Fig. 6) the static-dynamic opposition is present through the inert shape on the left, whose solid consistency contrasts with the airy background. The metaphor of the rock and the wind comes to mind: one immobile, ageless, the other active, transient. Jones’ air is enlivened by a multitude of flying marks – snow here enacts the dichotomy of nature’s elements, assuming two distinctive states: the calm, static state when it covers the landscape or the animated state, falling in flakes from the sky. Both aspects we visually perceive as part of the same landscape. The cycle never stops, for millions of changes occur daily to the scenery, but we see it as a finite, perfect picture, like R; S. Thomas in The View from the Window.

Jones’ inspiration is channelled by silent introspection and a very personal reading of his favourite poets. Another one Jones mentions with special interest is the lyrical American writer Annie Dillard (b. 1945), whose Pulitzer Prize-winning Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (1974) had critics regard her as a modern-day mystic. In this exhilarating reflection on nature and its seasons, the reader follows a personal narrative highlighting one year’s exploration on foot in the author’s own neighbourhood, Tinker Creek, in the Blue Ridge Mountains, Virginia.

The narrator is determined to present the natural world as it truly is, not sentimentally or selectively. Therefore she is as likely to reflect on a frog being sucked dry by an insect as on the angle at which sunlight strikes a certain springtime tree. She unties a snake skin, witnesses a flood, and plays ‘King of the Meadow’ with a field of grasshoppers. Her wise writing reminds us that events this simple are true gifts from the universe or the Divine for that matter. Therefore her philosophy is thus very similar to Basho’s. Obviously, Jones adheres to this line of thought and aspires to gain knowledge from the minutest things in nature.

The freshness and enthusiasm of Dillard’s writing fascinate Nicholas Jones. Although her angle is unique, he feels he can relate to the way she perceives nature mostly through her senses. However, Dillard also spends a great deal of time discussing vision and perception. For our analysis about the different ways of seeing, it is important to mention the story she recounts from a book about various experiences of people who, through surgery, gain vision for the first time. Some of these patients describe their first impression of the visual world as “a lot of different kinds of brightness” 8 or “an extensive field of light, which everything appeared ….in motion.” 9 Dillard describes a young patient’s first visit to a garden after her sight was restored:

She is greatly astonished, and can scarcely be persuaded to answer, stands speechless in front of the tree, which she only names on taking hold of it, and then as ‘the tree with the lights in it’. 10

The girl first notices luminous dots which seem to be suspended on a green mass. Her attention is drawn to the sunlight glistening on the shiny leaves. She is fascinated by elements which normally count as details to a person with healthy sight, for somebody who has grown up with the stereotypical notion and image of a tree. Dillard seeks this raw, unmediated experience of nature. She speaks of her quest to see “the tree with the lights in it” and how she spends time trying to see things just as patches of colour, as the basic, unfiltered, data. When she is not scrutinising Tinker Creek, she quotes her favourite books and authors and it was German doctor Marius von Senden who collected cases of adults who received their sight for the first time after cataract operations in his book, Space and Sight (1932):

One patient called lemonade ‘square because it pricked his tongue as a square shape pricked on the touch of his hands. 11

The senses of touch, taste and sight thus merge into a single synaesthetic experience and they cannot differentiate between them. More often than not, however, the long-term delight surgeons expected from the gift does not work out. The added sensory load is difficult to deal with and hard to ignore. For many, the flood of colours, forms and movements is impossible to decipher, yet is enough to know what they are missing, which is confusing and unsettling. Nevertheless, the unique sensorial associations are notable. Most of the eye patients see only flat areas of colour. Dillard realises the potential of these people and regrets missing the opportunity of their sharing their extraordinary vision with the rest of us:

Why didn’t someone hand those newly sighted people paints and brushes from the start when they still didn’t know what anything was? 12

Abstract landscapes produce images of similar quality. Jones’ art is in itself the unimpeded transcription of his imagination, superimposed on his surrounding environment. In his abstracts, whole areas of nature can be covered in one big blob of colour and perspective becomes ambiguous. Vivid patches catch the eye and are brought forward, whereas neutral ones melt into the undifferentiated background mass. In paintings like First of Autumn (Fig. 8), one has the impression that a clear photographic image could be obtained by simply adjusting the imaginary lens we are looking through. The blind person who receives sight for the first time needs to match a fictive image of reality to an actual one. The landscape is more sense that seen and everything is sieved through the individual’s sensibility.

For each new painting, the artist needs to see the world through fresh eyes. He shares the blind person’s excitement, confusion and struggle of putting the pieces of a mental jigsaw together to produce an image. A direct transition of this kind, from thinking and feeling to seeing can involve the overlapping of different sensorial faculties. Whereas for the blind person this manifests itself in the form of clinical synaesthesia, with Jones we have artistic synaesthesia, in the Symbolist and Baudelairian sense. The second type of synaesthesia which the artist undergoes is more voluntary and is actively cultivated through conscious repetition of the experience:

When I start a painting, I have no idea what it is going to be like when it’s finished. I don’t plan it beforehand in my mind. I just start with a set of colours and then see how it develops. I keep working till something suddenly comes alive, till it has the tingle factor, a certain feel. I would like to capture, for instance, the feel of the wind on your face or the sound of the skylark. A good painting could perhaps even make you smell: a dark blue, for instance, might smell sharp, fresh, crisp. 13

Let us see how Jones’ suggestion might apply to Frost Fields (Fig. 9). The juxtaposition of deep blue air against white ground brings forth mental echoes of arctic glaciers, frozen water and starless skies obscured by clouds of snow. This almost affects our body temperature and we may even be able to smell the distinctive, crisp smell of frost, which people growing up in colder climates may often associate with imminent snow fall. In spite of the fact that this is my personal, subjective aesthetic judgement, it may be one of the ways of following the artist’s view on experiencing his landscapes.

The landscape is first born in the artist’s mind. For this reason, the latter needs to be appropriately nourished. Having delved into the rich source of images and thought which the written word can supply, it is now time to look at some visual stimuli. Although Jones does not like being associated with any trends or traditions, there are a few painters whose work the artist admires and whose names he has carefully sought out:

Paul Nash (his magical vision), Ben Nicholson (his drawing and the structure of his compositions). Mary Newcomb (whimsical, quirky, quiet pictures of country life, interesting natural phenomena like light breaking through the clouds), Michael Andrews, Hiroshige and the Japanese prints, Matisse, Morandi, Klee, Picasso (for the life and joy), Calder, Bonnard, Friedrich, Vermeer and Eric Ravilious. 14

Although the list is especially varied, investigating some of the work of Jones’ favourite artists would explain several defining traits of his work and help towards a better understanding of his vision and techniques.

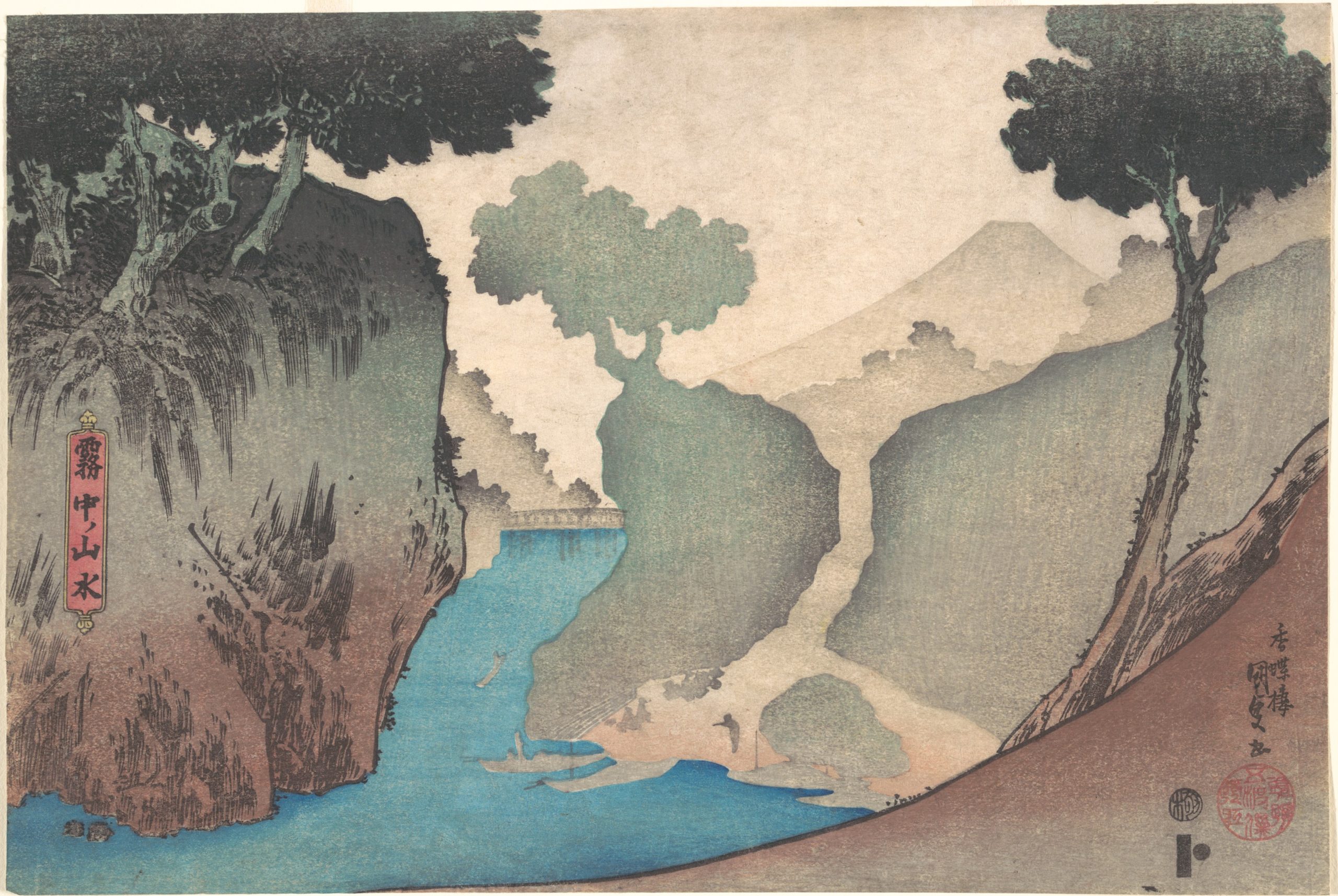

Chronologically, the Japanese prints come first. Having already mentioned Jones’ taste for the effective simplicity of Eastern art, it is hardly surprising to find that some of his images truly reinvent the visual poetry of the fukei-ga (landscape) woodblock prints. Jones admires their ability to immortalise an evanescent moment by preserving its natural freshness as opposed to amplifying it to grand proportions:

The way Japanese prints capture something very transient is absolutely stunning. They are perhaps a little like haiku. 15

Jones’ abstract (Fig. 10) and Utagawa’s print (Fig. 11) both capture stills of uninhabited landscapes. The atmospheric areas are emphasized in that they are juxtaposed with precise graphic accents, inserted mostly for the artists’ aesthetic pleasure. The source of lighting is very vague, whether it comes from the back of the picture in the Utagawa or from the front in the Jones. Both images tackle spatial ambiguities by means of blurred light. Utagawa’s depiction of fog is rather literal, although it successfully extends the space through the atmospheric perspective.

Meanwhile, Jones’ is a subjective, highly individual interpretation of nature. Here, the mist rising above what – through the poetic titling process – would later become the ‘water meadow’, is primarily an expression of a state of mind; his is very much a ‘landscape of the mind’. Even though still clearly figurative as far as the subject is concerned, on close examination one may, once again, notice that Jones’ landscape is the end product of the processual forces of the medium. There are areas in the painting, which, when isolated, have a certain spontaneous, gestural, almost ‘tachiste’ quality, displaying blots, stains and splashed marks reminiscent of the works of Wols, Hans Hartung or Georges Mathieu. Note especially the vertical strip in the bottom right corner, where Jones obtains a gritty-looking texture by covering the grazed ground pigment with a spray of tiny yellow dots. This is definitely a point of interest, an intriguing part of the picture, where pigment of radically different consistencies is juxtaposed – the soft, thick, foamy blanket of vapour is lifted to reveal the rough ground surface underneath.

As far as composition is concerned, one may observe the cropping of foreground forms, which is a distinctive Japanese legacy in European painting. So is the elevated view-point and the tilting of the foreground towards the viewer’s eye, which inspired most of the Impressionist landscapes. In both works our gaze is lead through the asymmetrically framed vista to a single vanishing point. The discoveries of the Japanese print makers reached Western painting in the late nineteenth century with Claude Monet as one of the main enthusiasts. Contemporary landscapes benefit from this influence as a natural progression. However, more than the rules of composition which have been naturally appropriated by most Western landscapists, Nicholas Jones aims to achieve the ‘crispness’ found in ukio-e images: the luminous, enamel-like colouring, the contours, the delicate atmospheric touches and precise calligraphy.

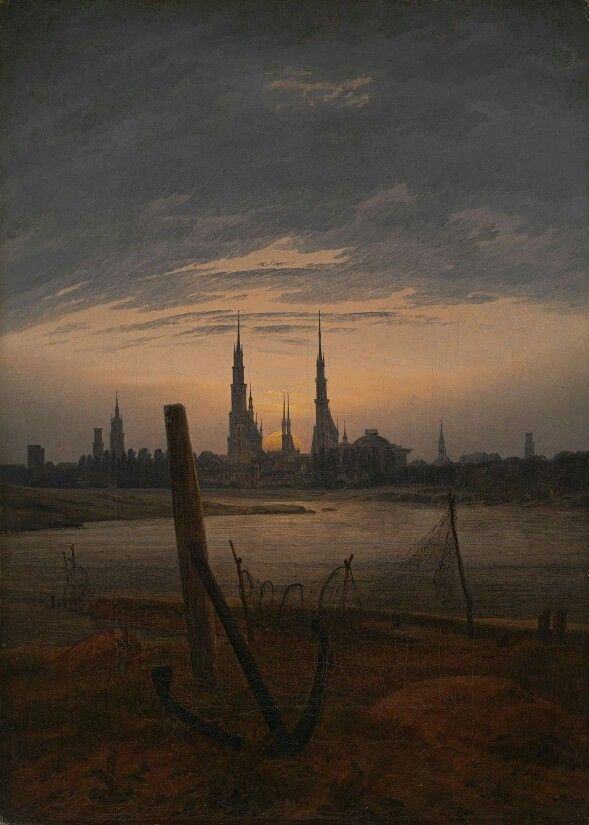

In the Northern European tradition, the stress was much more on producing emotionally charged landscapes. The German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich (1774 – 1840) famously reinvented nature as a metaphor for human mood in his symbolic vistas. Friedrich never painted directly from nature, and his paintings contain composites of different settings in wholly imagined scenes. He actually ignored the law of nature for aesthetic impact. (He would see his process as reflecting the higher coherence of Nature as large.) In some respect, Nicholas Jones’ abstracts relates to this artistic attitude through their main emphasis on visual impact.

Many of Friedrich’s paintings portray the earth undergoing transformations at dawn and sunset, or in fog and mist, often alluding thereby to the transience of life. Whilst his symbols usually demand intellectual decoding, this analysis focuses more on the technical delicacies the artist attains in his studies of light effects. These affect the viewer on a sensory level, delivering a frisson of ecstasy or alarm. The illumination he achieves has a certain theatrical quality. A number of Jones’ landscapes (e.g. A Break in the Rain, Last Light, Night Surf) display a similar luminous intensity. In As the Day Settles (Fig. 13), the painter uses equally dramatic contrasts of light and darkness and glazed, melting pigment, like Friedrich in his desolate City at Moonrise (Fig. 12). In Jones’ landscape, we have the same glowing sky reflected in a lower plane and very subtle gradations of pigment.

Jones’ work thus preserves the painterly quality of the Romantic landscape, working oils in the most traditional way, although object symbolism is now replaced by the abstract subject. In Friedrich’s City at Moonrise, the sun rising from behind the church towers is a symbol of hope for the endurance of Christianity. In contrast, there are no familiar shapes hiding coded messages in Jones’ work. In fact there are no delineated shapes in As the Day Settles whatsoever – instead, textures and light reflections create areas within the painting and these are to be interpreted as containing deeper meanings of an abstract kind.

In England, J. M. W. Turner painted in the same Romantic manner. Nevertheless, he managed to go beyond the significance of the portrayed subject and revolutionise our way of looking at nature altogether. His technique of dissolving forms in light and veils of colour was to play an important role in the development of the French Impressionist landscape. Looking back on the overall evolution of painting, however, we may find that Turner did more than initiate a new style of depicting nature – his work was the first to touch upon abstraction in the history of Western art.

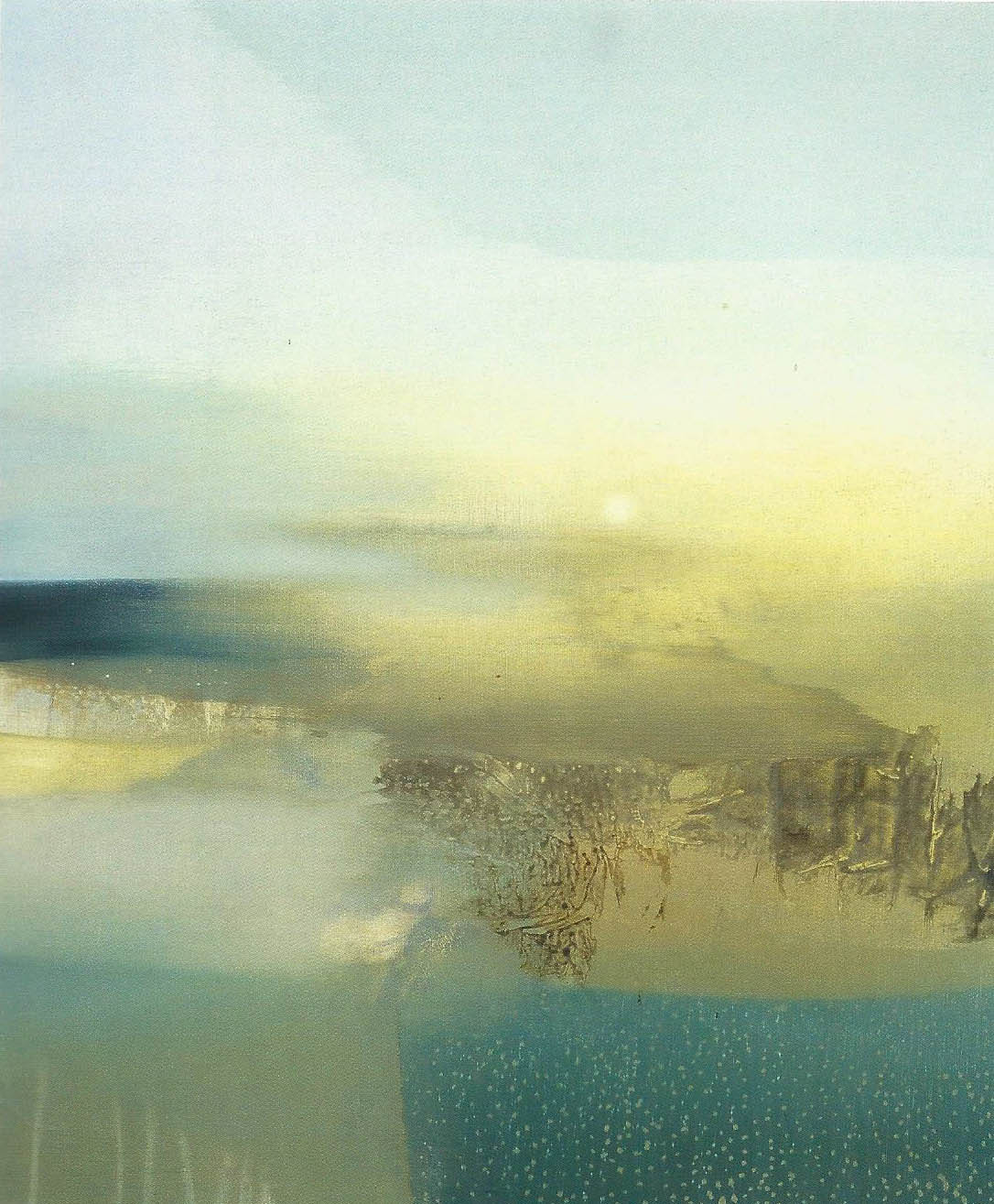

When contrasting Turner’s landscapes with contemporary works, one cannot help being amazed. If we compare Sun Setting over a Lake (Fig. 14) with Jones’ The Face of the Waters (Fig. 15), we notice how colour becomes light in both paintings. From Turner, Jones learns to dissipate pigment delicately in order to produce a layered atmosphere. In both works, our gaze is pulled towards the back, into the diaphanous distance, where the light circle of the sun becomes the vanishing point. Turner’s landscape is more an Impressionist study of a time of day (dusk), reminiscent of Monet’s Thames paintings, where the glowing light of the setting sun is diffused through thick smog. This study is based more on the observation of a real sunset, with Turner eliminating, or ‘editing out’ details that would upset this glorious spectacle of light. While Turner still uses nature as an actual reference, even if only as a pretext for his vision, Jones does not have a real image as a starting point. His pictures are projections of mental landscape experiences.

At the same time, Jones’ landscape is much more stylised and worked for a mainly aesthetic purpose; various technical effects, such as dotting, peeling, dripping and lustering of the painted surface, as well as its clear division into compositional entities, combine in a visually pleasing and balanced picture. The artist reveals his vigorous, hands-on painting process:

I mostly work the canvas on the wall. But at various stages of the painting process I will put it on the floor so that I can pour, drip, splatter paint on. I put plastic sheeting on top of paint and peel it off again, achieving various effects depending on how thick the paint is. Using newspaper in the same way gives a slightly different result. I work over some areas, particularly skies, using big flat varnish brushes to create very soft luminous effects. Occasionally I might wash some of the image away with turpentine poured over the canvas. 16

This is not how we imagine Jones conceived his ethereal landscapes. When completed, these works give the impression of having been tackled with care, paying special attention to every single detail. In The Face of the Waters, for instance, it would probably never occur to us that the earthy textures in the foreground could be obtained by simply peeling off sheets of paper or plastic. It is as if Turner were suddenly given buckets of paint and decorator’s brushes. Thus, Jones very successfully combines the traditional painterly approach and that of the contemporary process painter.

Anyway, what is it that makes one see either of the two paintings as abstract? Turner and Jones are very similar in that they both work the paint to a perfectly smooth and vaporous consistency; and because there are hardly any references points within the picture, distances are very hard to judge. The atmosphere they create is thus both vast and impenetrable. In this respect, Turner’s painting is far vaguer and therefore more abstract. Although Sun Setting over a Lake is considered to be one of his late unfinished works, the desire for simplification is obvious; nothings obstructs our gaze from slowly gliding through the cone of light towards the fire-ball of the sun. We also imagine Tuner’s work to be a more spontaneous product than Jones’ – we picture him painting frantically, instinctively building up pigment, trying to mix fiery hues on his palette to capture the blinding intensity of light.

In the light of his discussion it has become clear that Nicholas Jones is more of an aesthete than other abstract landscapists. His painting is about achieving a visually harmonious image, where colour, technical effects, depth and fine surface marks, all contribute equally.

I don’t have a conception of what the picture will look like when it’s finished. It very much evolves through the process of painting. I start with a colour scheme or a shape. Basically, I’m trying to get something interesting to happen. I just want it to come alive. It’s like going on a journey when you don’t know what you will discover. It is an intense process. I tend to work on a set of between six to twelve canvases at a time. Initially, I will work on them each one day at a time. Once I have started all twelve I come back to the first one again. By the time I’ve returned to the first painting the paint is dry and I can see what needs to be done more clearly.

His landscapes are born of a predominant longing to capture an elusive kind of delicate, transient beauty. Hence the association with the Impressionists. From a technical point of view, the artist works very similarly, but without making use of a direct, plein-air subject. Distinctive patterns and textures develop in his work, but they do not describe a determined pre-existing form, they just exist for their own sake. If the Impressionists painted to satisfy visual pleasures, Nicholas Jones may do the same, but without defining or referring to anything in particular. He admits to working round a general landscape theme and his titles allude to forms found in nature, yet his compositions are, in the final analysis, no more than fantasies of nature.

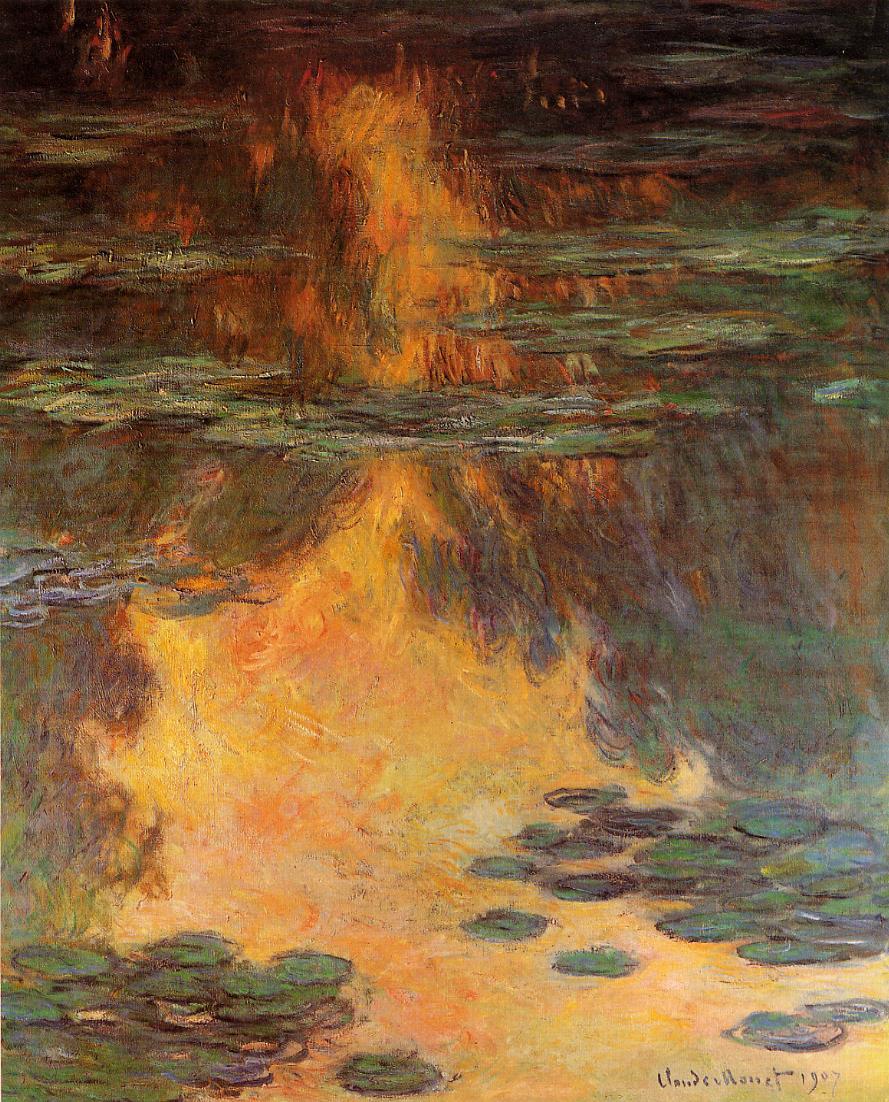

Let us compare an Impressionist landscape (Fig. 16) to an abstract one (Fig. 17). Monet’s forms are still largely recognizable, even if the painter obviously plays with image reflection and object repetition, achieving a semi-abstract pattern. Monet is greatly ahead of his contemporaries with the Water Lilies series, which magnify details from nature and focus on one single spot. By losing its context, the detail acquires an ordering structure of its own – its constituent parts start working together independently. The scale of the 1917-19 Water Lilies exhibited in 1955 at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, was most impressive; huge stretches of painting surrounded the spectator, who felt like being part of a new kind of reality. As an anonymous, but eloquent writer said:

Monet’s conception was undoubtedly influenced by the scale and format of the pairs of multi-fold Japanese screens that could then be seen in Paris. In such screens mist or clouds evoke a dissolving, fluctuating space. Sometimes the central panels seem to be empty, yet they draw the spectator into an infinite space. 17

The American abstract painters’ attention turned towards the innovations of Monet. Thus, the objective, predominantly geometrical type of abstraction of the Abstract Expressionists proved not to be the only way of working a massive surface. As a result of this late influence, suggestion was reintroduced into (abstract) painting. The artists credited with this were the group called ‘Abstract Impressionists’ (Hyde Solomon, Paul Jenkins, Philp Guston, Joan Mitchell et al.). It is worth recording that the notion of the ‘abstract landscape’ was first ever mentioned when defining the painting of these artists. When asked if nature had any serious relation to his work, Paul Jenkins (b. 1923) replied:

We are so inextricably bound up with nature that we cannot help but be affected. To what extent one is drawn to it objectively always remains the difficult question. For me, to approach it directly would be a self-conscious act of painting ‘at’ it or ‘about’ it. It is the very abstract elements of the sun and the moon, however, that dictate a visual demand in my painting experience. One radiates light, and the other reflects light. With the concept of reflection and radiation, one is not limited. 18

Suggestion sneaked into abstract works when the artists rediscovered light as a means of creating space within the picture. And light was definitely the gift of Claude Monet to abstract painting. Paul Jenkins called himself a ‘phenomenalist’ because his tool, light was a natural phenomenon. As an attribute of objective reality, it is in fact the only actual reference to nature in these works.

Almost half a century after the discoveries of the Abstract Impressionist, Nicholas Jones continues to play with light, trusting in its effects to shape his landscape. Viewed alongside Jones’ abstract, Monet’s Water Lilies Fig. 16) has a prevalent contemporary ‘feel’, the painter almost entirely relying on the evocation of reflections and texture. The space between water and sky is compressed and captured in the mirrored image. Jones’ Dawn, Woodland (Fig. 17) is based on the same principle, yet whereas Monet’s work is still a piece of cropped reality, our artist’s work focuses much more on creating space within the framework of an abstract composition:

I like to create space within my paintings. Using water, particularly in the bottom half of a composition, is a wonderful way to do this. Because of its reflective properties the whole canvas can be filled with light. 19

Nicholas Jones’ 2004 exhibition, Travelling Light, was centred on this concept. One of the few contemporary artists our painter speaks very fondly of is Mary Newcomb (b. 1922). This time it is not a matter of an influence of a technical sort, but a mutually warm, humane outlook on the environment. Newcomb ran a farm for many years, sketching rural scenes and ceremonies and producing strikingly poetic paintings. Scale and perspective could run riot in her pictures, but these quirky works have always been rooted in solid science and acute observation. Like Jones, Newcomb is a lyrical painter with a candid, unspoilt eye for reality. (Fig. 18)

The very quality Jones admires in Basho’s poetry and Dillard’s stories he finds again in Mary Newcomb’s work. These are all artists who take pleasure in and inspiration from small things, forgotten corners of nature, banal details nobody else would seriously consider. Nicholas Jones’ images thus surprise an idyllic side of nature. The ordinary becomes extraordinary when, eyes wide open at his inner visions, the artist rushes to record them, sharing his joy of life and nature with us. (Fig.19)

By no means is it sensible to define a painter’s work as ‘beautiful’, especially in our day and age, when the concept has been almost completely eradicated from most aesthetic theories. There is, however, no better or fairer formula, when the work is a truthful reflection of the artist’s inner world. Success is not about being a major or minor artist. It is about getting a work absolutely right by one’s own values, and Jones does that superbly. With his own intimate universe as his main reference and inspiration, he only has himself to outdo with each new piece. Driven by quiet determination and an endearingly ironic sense of self-worth Nicholas Jones will keep presenting us with generous samplings of his sensibility, which we can only look forward to.

Dr Imola Antal Mavity

Dr Antal Mavity is an art historian. This text was written in 2003 as part of her Phd. thesis on post-war landscape painting and abstraction.

1 The Works of Ruskin, ed. Cook/Wedderburn, vol XIII: The Harbours of England II, Turner’s works at the National Gallery 2

2 Imola Antal: Interview with Nicholas Jones, 23 July 2003

3 Imola Antal: Interview with Nicholas Jones, 23 July 2003

4 Imola Antal: Interview with Nicholas Jones, 23 July 2003

5 Eduard Hanslick: The Beautiful in Music, reporting of Cohen Translation, Bobbs-Merrill Co, New York, June, 1957, p.67

6 Imola Antal: Interview with Nicholas Jones, 23 July 2003

7 R. S. Thomas: Collected Poems 1945-1990, Weidenfeld and Nicholson, London, March 2001

8 Annie Dillard: Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, Harper Perennial Edition, N.Y., 1999, p. 26

9 Ibid

10 Ibid, p. 28

11 Ibid, p. 29

12 Ibid, p. 30

13 Imola Antal: Interview with Nicholas Jones, 23 July 2003

14 Ibid

15 Ibid

16 Ibid

17 From National Gallery of Australia: Monet & Japan. Reflections, weblink: http://www.nga.gov.au/monetJapan/Theme.cfm?ThemeUD=6

18 Paul Jenkins: ‘The Abstract Phenomenist’, The Painter and Sculptor, Vol 1, No. 4, Winter 1958-9

19 Imola Antal: Interview with Nicholas Jones, 23 July 2003