Nick Jones

Meeting Andras Kalman

A chance encounter with art dealer and collector Andras Kalman in June 1990 proved to be a pivotal moment in my life. This is the story of that meeting, and an expression of my appreciation for the unfailing support and encouragement that Andras showed me over the 17 years that I knew him.

When I first met Andras I had just turned 25 and was barely three years out of Art College. He was in his early 70’s (though his exact age he kept a closely guarded secret), director of the Crane Kalman Gallery and an influential and highly respected figure in the London art world.

The Story

When I look back over my life as a painter, meeting Andras was an encounter the importance of which it is hard to overstate. And yet, it could so easily not have happened. Though trained as a painter, I had spent the first two and a half years since leaving Art College working in stained glass, and had only been painting seriously for five months. Encouraged by the painter in the studio next door to mine, I decided (somewhat surprisingly) that it was time to find a gallery in London to show my work. So armed with some transparencies of my ten completed paintings, a few of the smaller canvases in the car, and my allotted portion of the confidence of youth, I spent a couple of days, traipsing around London and calling in on some galleries where I thought my work might conceivably fit in. Walking into a gallery can be an intimidating experience at the best of times and the thought of touting my wares in that way now fills me with horror. It was not a great success. Having approached in vain all the galleries on my target list, I decided, with a measure of relief, to relax and use the rest of my stay to see some exhibitions. One of these was an exhibition of paintings by Sir Matthew Smith at the Crane Kalman Gallery, on the Brompton Road.

I have to confess that when I stepped through its door, I knew nothing about this respected London gallery, and had never heard of its esteemed director Andras Kalman. I wandered around the show, enjoying the rich colour and effortless brushwork and was on the point of leaving when something surprising happened. Despite feeling that the establishment was quite out of my league, I felt inexplicably prompted to throw caution to the wind, and ask the elderly gentleman sitting at the antique desk (Mr Kalman himself) if he might look at some slides of my paintings. He very courteously agreed and, somewhat to my surprise, said that he would like to see three of the canvases if I might bring them into the gallery. (Headland, Rainswept Shore and Precipice.)

And so, a couple of days later, I returned with Headland (Fig. 4) and Rainswept Shore (Fig. 5). Precipice (Fig. 6) was too big for the car. Andras said that they were ‘difficult paintings’, but he liked them and asked me to keep in touch.

A few months later I sent Andras slides of eight new paintings of woods that I had done since my previous visit. Andras replied saying that he felt that the new work was a little out of tune compared with the usual sort of artists he dealt with, nevertheless he found Plantation and Firs ‘quite interesting’ and suggested that he might include them in a mixed show the following year.

In March 1991 Andras mentioned that he had vague plans for an exhibition in the summer of ‘Paintings of Silence’ (Winifred Nicholson, Mary Newcomb and others) in which he may be able to include a couple of my pictures. And so in May that year I came to London with a selection of canvases in a van. I brought Clearing (Fig. 7), Mountain Birches (Fig. 11) and 20 works on paper into the gallery. Andras spent a long time looking at Clearing, and putting it on the wall, but found it too dark. He looked at Mountain Birches, and studied the works on paper very carefully. He asked me about them: what are their titles? Are they a set? I felt my answers were rather stumbling and inadequate. He repeated that they were difficult paintings and would be hard to sell. He seemed uncertain; it was difficult enough getting people into the gallery, he said, let alone for unknown artists. I suggested that I bring Snow Fall (Fig. 8) and Under the Willows (Fig. 9) in from the van. Robin (now a director at the gallery) helped with the ferrying. On seeing them, Andras became decidedly more enthusiastic and positive. ‘Sit down and have a cup of tea’, he said before beginning to quiz me on where I worked and what my studio was like, where I trained, which journals I read, if I visited exhibitions, the price of the work, and so on. He asked me if I was all-right for money, and seemed rather surprised to hear that I was married (you look so young!) and to a doctor.

Robin mentioned that I had more paintings in the van, and Andras wanted to see them, so the three of us, carrying the canvases I had brought into the gallery, walked to Brompton Square, and had a viewing of Swollen River (Fig. 10) and the others against the side of the van.

Having seen all the work Andras said that he found the paintings very beautiful and that he would like to give me a show. He asked me to go away and think about it and let him know. He urged me not to agree anything with other galleries without speaking to him first. Before we parted he repeated his offer of a show and said that as a sign of his good intentions he would buy three works when I had done a few more canvases. He then tentatively suggested that perhaps I could include a bit more colour as ‘a little bit of light relief’. Nevertheless he said he found the paintings very romantic and moving.

Though the promised exhibition did not materialise for some years, Andras bought Mountain Birches and Outback in June 1992 and took Snow Fall, Willows on the Bank of a River in Flood, Burning Up and Under the Moss on a sale or return basis.

The early years of the 1990’s were a difficult time for the gallery with the recession, his wife’s illness, and his own health issues. Nevertheless, Andras kept an eye on what I was producing and identified the paintings that he felt looked good and urged me not to be discouraged, even if he wasn’t able to help me as he might have hoped to do in better times. And so began an association with the Crane Kalman Gallery that has run ever since.

Reflections

Over the years until his death in 2007 I would call in at the gallery four or five times a year. When I arrived Andras would get up from his chair to greet me. He would grip my hand in both of his whilst looking intently into my eyes as if he were searching for something. I felt that he liked me and was genuinely pleased to see me. He always asked after my wife and children and, on one occasion when I brought our three young children into the gallery to see one of my exhibitions, he spoke to each of them asking which of the pictures they liked the best.

Not surprisingly I was very much in awe of Andras and I found my visits to the gallery strangely stressful. I felt rather uncomfortable and was uncertain quite ‘how to be’ in that environment. I suspect that Andras sensed something of this, and accepted it in a fatherly way whilst gently seeking to nurture my self-belief and facilitate my unfolding journey as a painter. Looking back, I wish that I had been able to be more fully present in his company, and had got to know him at a deeper level.

Andras always gave me space to find my own path as a painter. He was unfailingly supportive and though he didn’t hesitate to speak his mind, any guidance that he gave was always offered with a very light touch (as with his repeated encouragement that I contemplate touches of red and other vivid colour, which I long resisted.)

A number of other artists whom Andras ‘discovered’ and whose work he showed had also walked into the gallery unannounced off the street, most notably Alan Lowndes and Mary Newcomb. I am intrigued by what it was that Andras saw in those early works of mine (or in me) that led him to be so supportive from the first.

Philip Vann noted in Andras’ obituary in the Guardian that what drew many people to the gallery was a ‘subtle, unsensational, contemplative quality’ to the work that he showed. Vann refers to the ‘Silence in Painting’ exhibition which finally took place in 1999 to mark the galleries 50th anniversary and describes ‘the resounding quietness’ manifested in landscapes of Giorgio Morandi, abstracts by Nicholson, and the spacious, luminous paintings of Mary Newcomb on display.

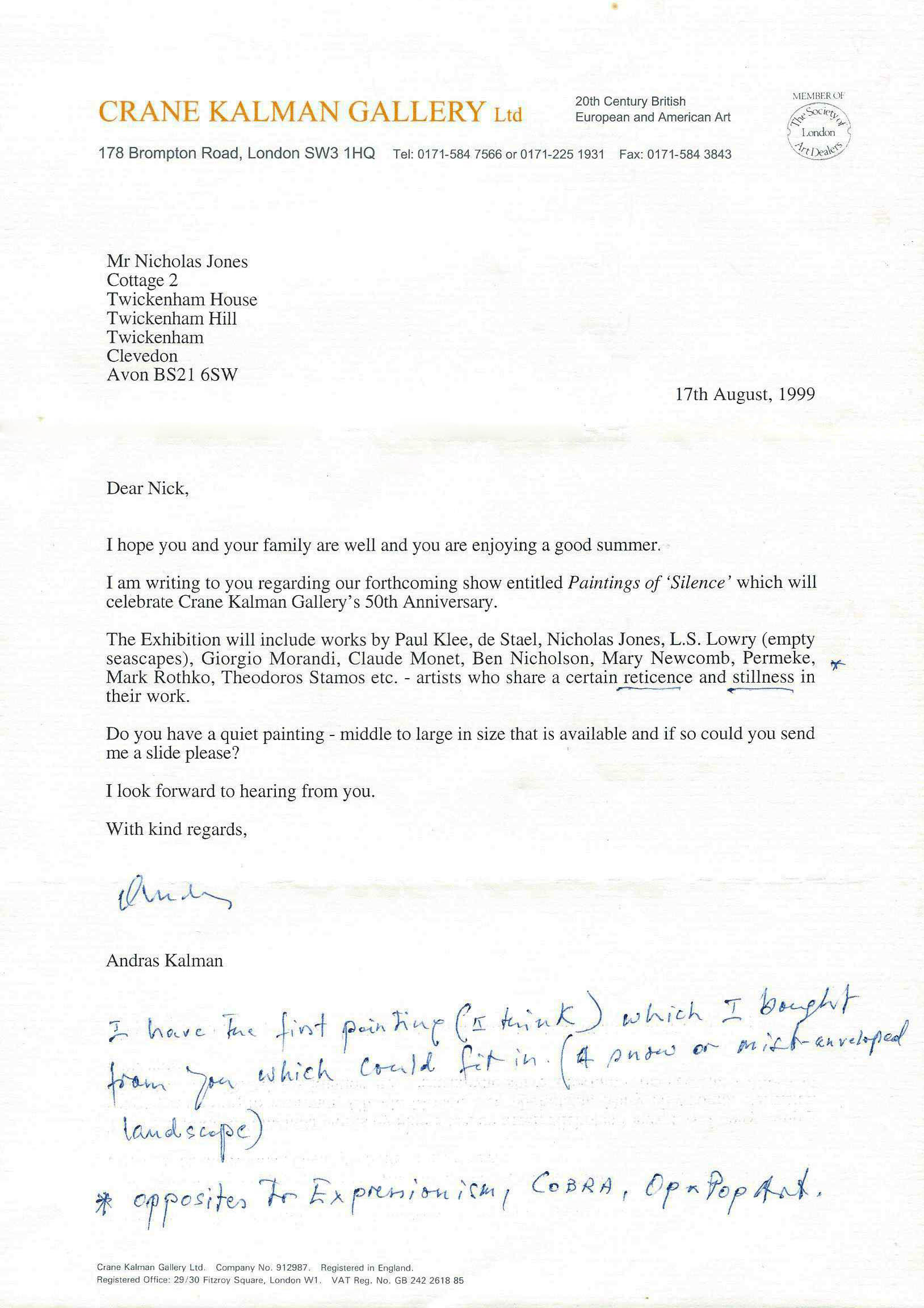

Indeed, in Andras’ letter of 17th August 1999 (Fig. 12) asking if I had a ‘quiet’ painting for the ‘Silence in Painting’ exhibition, he explained that the artists he intended to include (Klee, Morandi, de Stael, Monet, Rothko, Nicholson, Lowry, etc.,) all shared a ‘certain reticence and stillness in their work’. Looking back I now wonder if on those first visits to the gallery, Andras discerned a quiet reticence in me that was beginning to manifest itself in my work even at that early stage of my development as a painter, and that he felt was worth nurturing.

Though I would have considered ‘quiet reticence’ to be a positive personal attribute at the time, I now sense that some of what may have come across as reticence was more to do with my rather unformed and indistinct sense of self. For many artists painting is a way of making sense of life, and that was the case for me also. I was trying to find out who I was. Not surprisingly, the route took many twists and turns, some of which led to work that was not so in harmony with the usual kind of paintings that Andras showed, and in which quiet reticence was not so clearly on display.

In time I began to settle in on abstracted landscapes that evoked a sense of spaceous stillness and quiet. I now recongnise that these paintings were less an expression of an inner state that I already possessed, but rather a compensation for something I lacked and was desperately seeking. This perhaps explains the sense of disconnect I sometimes felt when seeing my paintings hanging in the gallery, either in the excellent company of a Crane Kalman mixed show, or taking over the whole space in a solo exhibition.

Of course, at the time, I was not consciously aware of any of this. I was simply following the powerful inner urge to paint, and in the rest of life was muddling by as best I could. I am so grateful that Andras stood by me through the various twists and turns of my journey. His belief in me helped carry me through. I was often surprised just how much he seemed to believe in me.

For the last few years of his life Andras had my round canvas ‘The Abundance’ (Fig. 13), with its sought after splash of vivid red, hanging by the chair at home where he used to watch Wimbledon on television. (He had been a professional level tennis player in his youth). It is comforting to think that my painting was, in some small way, keeping him company as he became frailer and approached the end of his extraordinary life.

In an interview with Charles Hall in the October 1993 edition of Art Review Andras said that,

‘A few artists I have shown have, alas, simply faded out. One of the things that you learn if you’re in the business for 40 years is that just supporting young artists is a worthy but misguided practice. Nine times out of ten they don’t have the aesthetic stamina, the imagination, or discipline to be endlessly refreshing. You ought to support artists of real quality. Artists make the mistake of thinking that galleries are hostile to them, but I wish I could find more marvellous talents. I would run after them.’

Those words have always stayed with me, but not in a heavy way or with any sense of pressure. Rather, they focussed my intention to joyously live up to the trust and belief that Andras placed in me, no matter what direction it might lead me in.

Nick Jones

June 2020